BE Meyers 40th Anniversary Video

Form follows function. It’s an adage that holds true for the majority of well-designed things. Yet form is a function in and of itself, and when given equal weight to a project, there’s the opportunity to really move beyond the restrictions of what a project could otherwise become.

Combat B-Roll

In March, Shawn Nelson and I, were given the opportunity to tell the story of BE Meyers. A company whose product could best be described as that of science fiction. Lasers only visible to optics that magnify light a million times over, systems built for warriors who operate in the darkest recesses of the world, who do very bad things to very bad people. This is a company that brings high technology, to low-tech situations, and has been doing so for 40 years. Like many in the defense industry it’s all too easy for companies like these to see video as a burden, something that must be done because of the complexity of explaining their story and products. The end result often ends up as one of frustration for the stakeholder’s, and not an experience of storytelling they jump into with excitement. It becomes easy to end up with something that lacks emotion, scope, and quality of execution. Regardless of what industry it’s for, corporate work has a tendency to be all about function, telling the facts, without being an entertaining story that stands on its own.

BE Meyers IZLID Ultra(s)

We were pleased to hear from the outset that our client wanted to avoid these pitfalls, which put us in violent agreement with them, as we wanted to focus on telling a compelling story with equal parts visual execution. The biggest step in this process was to contextualize what the products do, and how to show them in a manner that was as highly cinematic. This execution was informed by working with the client to really flesh out the scenarios that best exemplified each product, and would serve as b-roll that in and of itself could be described as mini-movies. Normally b-roll is a functionary product that works for cutaways, often times becoming visual filler, whereas here we wanted to really give it as much weight as the a-roll it was supporting.

JTAC Mountain Storyboards

BE Meyers // Look Book

We found that using ‘look books’ and cinematic references helped to both establish the look and feel, but also create and elevate the bar that we wanted to achieve visually. A big part of this was long exposure wartime photography, and low-light cinematic sequences from films like “Lone Survivor.” We also storyboarded extensively sequences where we would not have the chance to really rehearse, or where components would be in flux (such as how many people there would on screen, or what vehicles would be available to film). This allowed us to have a clear idea of the angles we would need regardless of the changing circumstances, rather than getting distracted by what differences we would have to deal with at production. More importantly these storyboards and cinematic touch points would enable us to help bridge between what the client needed, and what we wanted to execute. This clear line of communication would pay for itself a thousand times over once we attempted the cinematic b-roll, which comprised half the entire production.

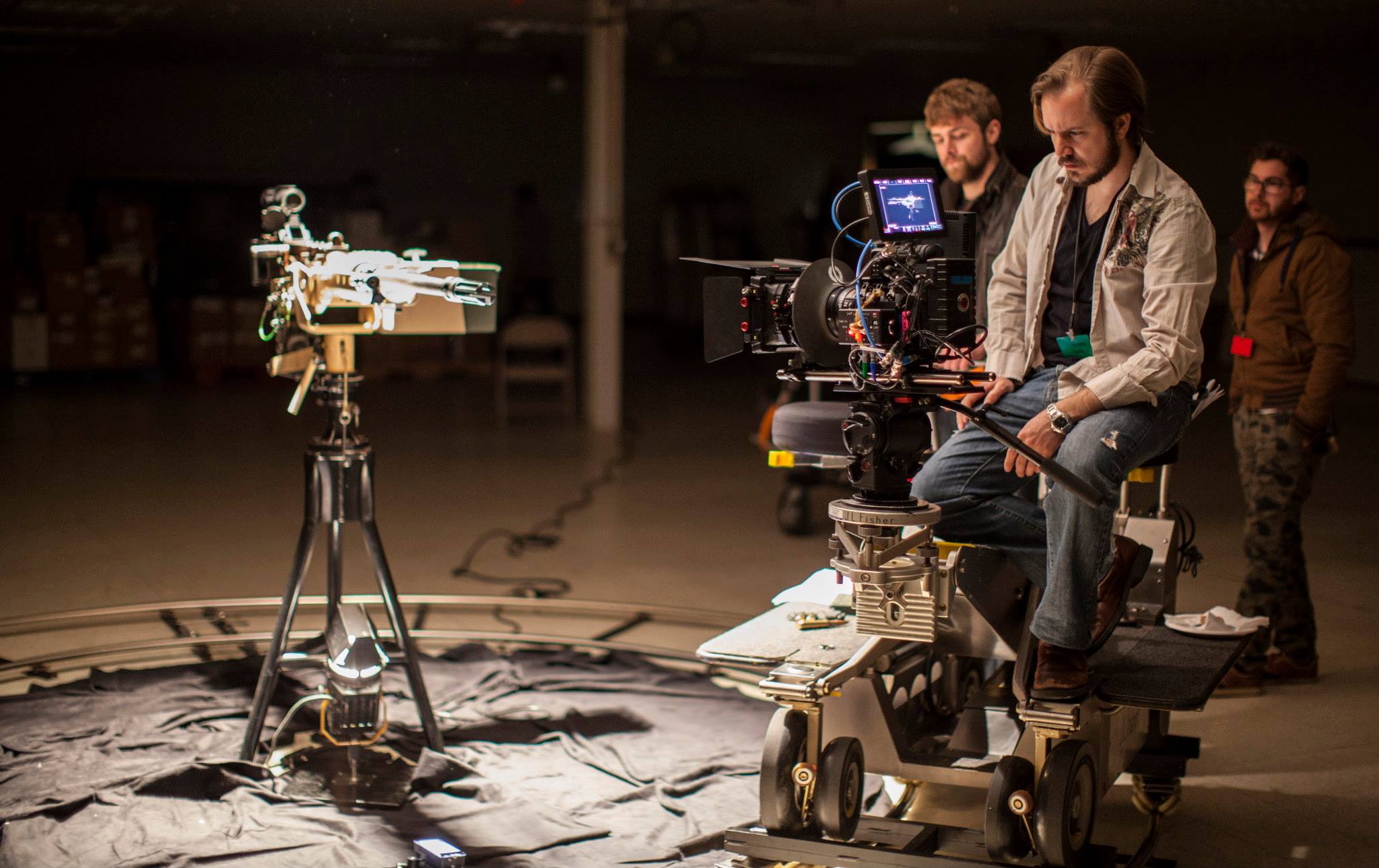

Shawn Nelson providing input on framing.

Logistical Warfare

The entire project filmed over the course of 4 days. With 2 days in the BE Meyers HQ, and 2 days offsite in the wilderness. This presented an extremely aggressive schedule, which required a lot of moving pieces with a lot of safety nets in regards to execution. Days 1 and 2 were treated very much like a corporate piece, but shot in a way more reminiscent of indie film production. This meant an extremely efficient and small crew, in an extremely mobile package. For almost all of these two days the camera moved around on a JL Fisher 10 Dolly, which allowed us to quickly re-evaluate framing, but introduce motion into our shots that would have otherwise required more time to bounce between tripod and slider/dolly. This one tool both presented a fantastic platform to improvise without penalizing the director of photography and the director on their creative decisions, and it also served as a psychological boost for the employees and key executives at the company. Specifically it lent an air of Hollywood, and helped to reinforce their decision that just because this was a corporate story it could also be given the reverence and scale of a commercial/small film.

In addition the dolly also allowed us to create a couple of key signature on-camera effects that would otherwise be too complicated to achieve otherwise, or would have to be handled via computer animation. Specifically we wanted to quickly and visually tell the story of a modular chassis system that works with the Browning M2 .50 caliber machine gun. This system enhances an already formidable weapon, and allows for the integration of laser and optics systems that BE Meyers either creates, or provides. To visually tell show each component we envisioned a 360-degree circular dolly shot showing the system building up, from the gun mount, to the chassis, to the gun, lasers, and finally optics. We also wanted to avoid doing this in computer animation, while that can afford more control over focus, angles, and lighting, also looks tends to look cheap, as there’s an authenticity present in having really filmed it on set. There’s a production value just in knowing that was really on camera, flaws and all. This was ambitious given the amount of time to set up this practical effect, but the end results are extremely unmistakable and extremely memorable. This was an effect that could have occupied an entire day of filming, but one that we were able to accomplish in mere hours. I will be covering the effects breakdown for this shot in a future blog post…

Casey Schmidt doing last minute lighting changes.

Days 3 and 4 were however a bigger challenge, and not one affected by amount of content, but by location and the logistics of herding cats. These days would serve are our military b-roll, and to accomplish this we adopted a very documentarian mindset. We were able to loosely script certain scenarios, but available vehicles, personnel, and geography would determine how they played out. Because of filming restrictions, such amount of vehicles just to haul personnel out to location, it meant that we worked with available light, and as minimal of rigging as possible. What was a single camera shoot for the past two days in a factory was now a three-camera shoot out in the field. Three RED Epic-MXs, and an entire series of ARRI/ZEISS Ultra Primes, being operated by Shawn Nelson (Director), Domenic Barbero (DP), and I (Isaac Marchionna / Co-Director). The working style was simple, huddle, establish a scenario informed by our storyboards, and then quickly figure out how best to maximize how we would create coverage.

But more than that our goal wasn’t to just provide angles, but to work from the mindset of “how would we shoot this if it were an action movie?” What are the angles we’d grab if we could spend hours lighting or rigging this shot? And once we did, how could we obtain a result that best approached that ideal execution in that narrow slice of time. Having multiple camera operators, variety of lens choices, and subjects (military members) trained to execute orders with impeccable accuracy all added up to give us everything we strived for on that day.

RED Epic MX(s) with ARRI/ZEISS Ultra Primes

Day 4 was going to be a challenge not because of subject matter, but because of the logistics of where we wanted to shoot and the problem of moving people and gear into a spot just to begin working. Day 3 took place about 90 minutes south of Redmond, WA, all on paved roads. Whereas Day 4 would be about 3 hours east and located on the side of a mountain, accessible only by off-road vehicles.

To compound the issue 90 percent of the required footage would be filmed from dusk until dark, which meant that daylight was precious for establishing a basecamp, ridding ATVs up the side of a mountain to scout our locations and create a shooting schedule, head back down, and haul multiple trips worth of gear up a rather steep mountain face, all the while chasing the light knowing we wouldn’t get another chance. Once again having a crew that was incredibly nimble made all the difference. Each shot had one major attempt, either we got it, or that shot was lost. Despite the hardship of hauling camera gear up narrow paths, frigid cold winds, the threat of rattlesnakes (of which we saw more than a few), we accomplished every single shot we sought to capture.

Dusk Filming

We couldn’t have done this without a great crew. But more than that we couldn’t have done it without a client who enabled us to do the kind of storytelling we thought the project deserved. Our client believed in the story we wanted to tell, and moved heaven and earth to provide us with the people and gear in front of the camera that created a level of production value that can’t be cheated. That level of authenticity pays for itself on screen. This was an incredibly challenging project, but an immensely rewarding one for everyone involved. Our goal was always to enable, and empower the client to create a scenario where their story could be told passionately. And in doing so lay the groundwork for vindicating video as a powerful tool that cinematically tells the story of their family-owned company, what they’ve done, what they do, and for what the future holds. The end result is that we were able to bring together multiple stories, multiple parts of a company, into one exciting and informative cinematic experience. And in doing so work to transcend beyond what could have otherwise been a purely functional corporate piece.